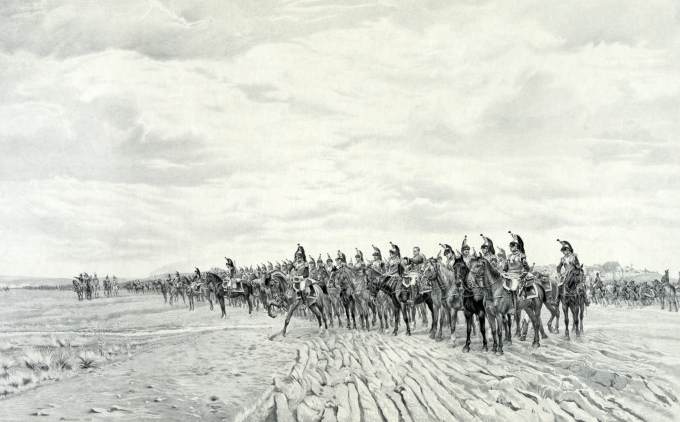

Jules Jacquet, Cuirassiers at Austerlitz (1874)

In a series of lightening campaigns against Austria and Russia, Napoleon led France to victory against overwhelming odds. The Battle of Austerlitz that occurred during the War of the Third Coalition (1803-1806) would forever change the shape of central Europe.

By Steven Knorr

The Formation of the Third Coalition (August 1805 – December 1806)

Since 1792, France had been at war with all of the major powers of Europe; though peace had been made with each in turn, Great Britain held out the longest. In March 1802, the Treaty of Amiens ended the hostilities between the United Kingdom and France. Europe seemed at peace. But conflict arose quickly as the British and the Swedes made an agreement that would lead to the forming of the Third Coalition against France. Russia and Austria would also join this coalition; Austria in particular was keen on revenge after suffering embarrassing defeats and ceding territory in the First and Second Coalition wars. The first two coalitions were waged against revolutionary France; the Third Coalition however would mark the beginning of what is now known as the Napoleonic wars. In May 1803, before these alliances were finalized, the UK declared war on Napoleon’s France. By August 1805, Russia and Austria had joined in and all Europe was again at war.

Europe, 1803. Map made from template here.

Napoleon, French Emperor after 1804, developed ambitious plans for invading the British Isles. He assembled a massive invasion force around 200,000 men for the task. But with creation of the Third Coalition and threats looming on the continent, Napoleon abandoned his plans of invasion and turned his attention eastward. Though Napoleon discarded his invasion plan, all was not lost. French troops gained invaluable experience in the months of training that would prove to be of service in their upcoming campaign.

The Ulm Campaign (25 September – 20 October, 1805)

The Austrians moved towards France by concentrating their forces near the city of Ulm, at the time part of the Electorate of Bavaria, a state in the Holy Roman Empire. Karl Mack was the commander of the Austrian forces. He instituted reforms to the army on the eve of the war which would lead to insufficient officer training. This greatly hindered their military organization as officers did not have the proper training to coordinate troop movements. In the previous campaigns against the Austrians, the Italian theater became the primary focus for the French. The Austrians believed the French would focus heavily on Italy again and dispatched 95,000 troops into northern Italy and 72,000 into Ulm. The Austrians hoped with the heavily fortified and mountainous region of Ulm, they could hold out until Russian reinforcements arrived.

The Ulm Campaign saw the capitulation of an entire Austrian Army within the course of a single month.

France, along with its German allies, began the Ulm campaign on September 25th, 1805. Napoleon knew the main Austrian army was presently isolated in the German southwest and intended to engage it before it could be joined by the Russians. France began the campaign with 210,000 troops organized into seven corps; at the time the corps system of military organization was a uniquely French innovation. This army is what would come to be known as the Grande Armée. When the campaign began, the French forces crossed the Rhine and stretched over a 160-mile front. This was in line with the Emperor’s maxim: “separate to live [forage], unite to fight.” Marshal Joachim Murat led cavalry screens through the Black Forest to fool the Austrians into thinking the invasion was coming along an east-west route. Murat was followed closely behind by the V Corps of Marshal Jean Lannes. The main attack in Ulm would be supported by attacks on other fronts, such as Naples and northern Italy. Napoleon’s plan of attack was to envelope the Austrian army with his full force.

By late September, the entire French army had crossed over north of the Austrian army, turned eastward and moved the Austrian right flank. Karl Mack’s field intelligence was very poor and he did not realize the extent of French movements. On October 6th, Napoleon had put infantry and cavalry divisions across from the Austrians on the North Bank of the Danube to prevent any chance from escape. Mack finally realized the danger of his position and decided that he must go on the offensive. In an attempt to prevent the Austrians from taking a strong position on the Danube, Napoleon sent Michel Ney’s VI Corps to Günzburg, though he did not realize that Mack was moving the bulk of his forces to that location. The VI Corps, in its position north of the Danube, would see repeated action and would play a particularly important role in the Ulm campaign.

The first battle of the campaign, Wertingen, was fought on October 7th. An isolated Austrian division, led by Auffenburg, was overwhelmed east of the main Austrian body when discovered by Murat’s multiple cavalry divisions. As they were assaulted by French cavalry and outflanked by arriving Grenadiers, most of the Austrian division was either killed or captured. The battle cut off Mack’s larger army from retreating eastwards, and he was forced to move north along the Danube to Günzburg, where Ney’s VI Corp had just arrived. Ney had sent a division to capture the bridges leading to Günzburg, where they took prisoner 200 jaegers, Austrian light infantry that had been sent ahead. In response, the Austrians reinforced their position around Günzburg with three battalions and 20 cannons. Though the Austrians repelled several assaults from the VI Corps, the French ultimately prevailed with the arrival of a delayed infantry regiment and were able to capture the Austrian side of the Danube. After Günzburg, Mack ordered the Austrian army to retreat back into the city of Ulm.

By October 10th Napoleon began to seriously consider the Russian threat looming in the east, and did not know that the Austrian army was still concentrated at Ulm. More than half of the French army (the I, II, III, and IV Corps) was moved east, dangerously far away from Mack’s forces. Napoleon dispatched Murat to his right wing, with Ney continuing his push southwards towards Ulm. Only the V Corps (Lannes), Murat’s cavalry, and the VI Corps (Ney) remained on the Austrian perimeter. On October 11th, unsupported, Ney attacked southwards. As Ney moved his corps, an isolated division discovered the bulk of the Austrian army and was attacked at the Battle of Haslach-Jungingen. The division bravely held off the attack after suffering terrible losses, but Ney was forced to retreat.

These events alerted the French army to the fact that the Austrians were still concentrated around Ulm. Napoleon moved quickly. Still deeply concerned about the Russian threat, he sent the I, II and Bavarian corps further east to Munich. The remaining corps were sent out to the guard bridges out of Ulm, and corps were moved to the north and west of the city

Austrian leadership was in total confusion; Mack still did not comprehend French movements and issued contradicting orders to his officers. The Austrians were blocked from the north and east by the French, and by the River Iller to their west. By October 13th Marshal Soult’s IV Corps took territory at Memmigen, preventing Austrian retreat from the south. Desperately, two groups of Austrian forces tried to push north to the Danube and break out. At the battle of Elchigen on October 14th, Ney’s VI Corps forced an Austrian Corps north of the city back south into Ulm. The other Austrian force, Werneck’s division, was able to escape the French net by pushing further northeast with heavy artillery.

The Battle of Elchingen, 14 October 1805. Austrian forces surrendered six days later.

The French continued to close in. Nearly 5,000 Austrian soldiers surrendered to Soult south of the city. By October 16th, the entire Austrian Army was encircled by the V, II, IV, and VI corp clockwise around Ulm. The final battle for the city of Ulm was on as French and Austrian forces clashed around the city. Mack’s command was in chaos, and Austrian troops were despondent. Austrian Archduke Ferdinand, subordinate to Mack, saw the writing on the wall. Against orders, Ferdinand directed all Austrian cavalry to flee Ulm to meet up with Werneck’s forces. The cavalry were viscously harried by Murat, and only a small number made it to their target.

Werneck’s division attempted to attack the French V Corps from the north, but was defeated and chased by Murat’s cavalry. After a series of unsuccessful small battles, Werneck surrendered to Murat on October 19th.

Ulm had been brought within range of French artillery who began shelling the city. Mack held out for hope of reinforcements, but news of Werneck’s surrender was the last straw. On the 20th of October, Karl Mack surrendered to Napoleon, and 30,000 Austrian soldiers entered into French captivity. Twice that number had been captured through the entire Ulm Campaign, which lasted 26 days.

The Austerlitz Campaign (November – 2 December, 1805)

With the surrender of the Austrian army at Ulm, the French Army moved to capture Vienna. The disaster of Ulm compelled the Austrians to avoid conflict until their Russian allies arrived.

Napoleon wanted to feign weakness to draw out the allies to attack his army, and decided not to go north and pursue. He did everything he could to make the French army look like it was ready to collapse. Allied scouts counted 53,000 French troops at Austerlitz, almost half the combined strength of the Austrian and Russian forces.

What the Allies did not know was that an additional 22,000 troops were stationed within supporting distance of the French main army at Austerlitz. In addition, Napoleon sent General René Savary to the enemy headquarters to deliver the message that he did not wish to do battle. Savary was also tasked to examine the allied situation. The diplomatic mission was successful and an armistice was signed on November 27th.

Subsequently, the French withdrew from the town of Austerlitz. During their retreat, they feigned chaos in their ranks in order to lure the enemy onto the Pratzen Heights, the local high ground in the center of the French army line. The following day Napoleon met with the Tsar’s aide and personally expressed anxiety and hesitation. This too was part of the trap and many Allied officers supported an immediate attack against the French.

The Battle of Austerlitz took place on December 2nd, six miles outside of the town of Brunn and Austerlitz. The terrain of the battlefield was dominated by large hills that overlook the Brunn road and several small streams and villages. The central part of the battlefield was the Pratzen Heights, already given up by Napoleon. It gave the Allies a dominant strategic position on the battlefield. They were commanded by Tsar Alexander I and Francis II, though Alexander was an officer in name only. The real authority of the Russian army laid with Mikhail Kutuzov. It should be noted that the Russians had not adopted the military order of battle of the French or Austrians. Their military command still used the old regime style structure, with no units larger than the regiment level. This would greatly hinder the Russian military organization especially when compared to their French counterparts.

As the French intentionally left the Pratzen Heights and gave up the dominant center position, Napoleon was determined to continue to lure out the Allies into a full assault. He weakened his right flank hoping the Allies would attack there. The plant was this- when the Allies attacked his right flank, his concealed troops stationed opposite of the heights would attack en masse and recapture the heights. He would then have the Allied army encircled and deliver the final crippling blow in a massive assault. The final assault was to be conducted as soon as possible. Napoleon hoped to use the early morning mist to cover his hidden troops. To support his weak right flank, Napoleon ordered a Corp stationed at Vienna to make a forced march in time to save join General Legrand’s men on the right.

The battle began at 8 A.M with the Allies’ attacking the village of Telnitz on the French right, just as Napoleon had planned. This section saw very heavy fighting during the early hours, as Allied charges driving the French out. This village would switch between the French and the Allies’ over the course of the battle. The Allies were not attacking the right flank at the speed Napoleon desired. Cavalry detachments had been placed on the allied left and this slowed the Allied infantry. Though the allied planners thought this was disastrous, this proved to help the Allied army. The heaviest fighting of the battle took place at the village of Sokolnitz. Two units of French light infantry and a unit of skirmishers were stationed in the village. The initial Allied assaults proved unsuccessful, until allied General Langeron ordered a bombardment of the village which forced the French out and the village was occupied by an allied division. The French would soon counterattack and retake the village, only lose it again. Sokolnitz saw some of the heaviest fighting of the battle and like Telnitz, would change hands several times throughout the day.

It is at 8:45 when Napoleon had gained the confidence that the Allied center was now weak enough to attack. He asked General Soult how long it would take to reach Pratzen heights and Soult said “Less than 20 minutes, sire”. When Napoleon ordered the attack 15 minutes later he said “One sharp blow and this war is over”. Though the fog covered the French troops, they had to march up a slope into the defenders. Russian soldiers were surprised to see so many French soldiers. Many inexperienced Austrian soldiers joined the fight on top the heights which gave the Allies a numerical advantage on the advancing French. Regardless, a desperate bayonet charge by the French drove the Allies out the heights. To the north in an area known as Staré Vinohrady, Allied battalions were breaking due to deadly French skirmishers and volley fire.

Napoleon then turned his attention south where there was still fighting at Telnitz and Sokolnitz on the French right. In an effort to drive the enemy from the field, he directed St. Hilaire’s division and part of Davout’s corps to launch a two-pronged attack on Sokolnitz. Enveloping the Allied position, the assault crushed the defenders and forced them to retreat. The allied lines began to collapse which forced them to retreat. In an attempt to slow the French pursuit, the Allies used cavalry to form a rearguard. This was the last line of defense to cover the allied withdrawal.

Allied causalities for the battle total 36,000 out of an army 85,000 and the French lost only 9,000/ 73,000. This victory shows Napoleons tactical genius as he lured the Allied armies out into a trap and enveloped them. Austerlitz is often cited as Napoleons greatest battle. The allies failed to have the ability to perceive the trap, especially after the embarrassing defeat at Ulm where the Austrian army had also been surrounded. The Allies should have taken a much more cautious approach to attacking the French forces.

The Treaty of Pressburg (26 December 1805)- The New Order in Central Europe and Germany

The immediate outcome of the battle was the Treaty of Pressburg, in which Austria officially recognized the territory captured by the French in previous wars. Austria was to cede land to Wurttemberg, Baden and Bavaria. Venice, which had lost its independence to Austria in the Treaty of Campo-Formio (1797) was to become part of the Kingdom of Italy. Austria also paid 40 million francs as indemnity but Russia was allowed to withdraw its armies.

But the most important part of the Treaty was the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire. After a millennium of existence Napoleon had brought it to an end, and even after his final defeat in 1815, it was never brought back. The Austrian Hapsburgs surrendered the title, recognizing its impotence. In its place Napoleon would create the Confederation of the Rhine, which was a collection of German states excluding Prussia and Austria. After Austerlitz, the myriad territories which comprised the Empire were reduced to forty. The remaining states were greatly enlarged in compensation for land lost on the left bank of the Rhine (which went to France), and were allowed to absorb their smaller territorial neighbors. Baden was elevated to the status of a grand duchy, and Bavaria and Wurttemberg became kingdoms. The surviving small German states that comprised the confederation, grateful for their acquisitions, turned from Austria and looked to Napoleon for leadership. The Confederation states and princes would remain French allies until they followed the French onto the desolate Russian steppe almost seven years later.

Sources

- David G. Chandler, The Campaigns of Napoleon (1973)

- Brendan Simms, Europe: The Sruggle for Supremacy, from 1453 to the Present (2014)