From 40,000 BC to the Roman Conquest (15 BC)

By Nick Richwagen

The Austrian city of Salzburg is an international tourist destination. The city is best known known for being the birthplace of Mozart, as well as its Baroque architecture (17th-18th c.) and medieval history. Today, the city is home to 150,000 people and is the capital of Salzburg State (Land Salzburg), which encompasses almost 560,000 Austrians. Although better known for more recent history, Salzburg and the surrounding region have an ancient legacy reaching back into the stone age (with human habitation as early as 40,000 years ago). The town itself has Celtic and Roman foundations, and in the Middle Ages the town was an economic powerhouse and center of industry. The name Salzburg (“Salt castle” in German) comes from the rich salt reserves responsible for the region’s wealth in prehistory, medieval, and modern times.

It is worth considering the earliest people who lived in this area (including the Eastern Alpine region), and how they developed and thrived in a challenging environment. This article will look at Salzburg’s first inhabitants from prehistory into the Celtic period. In particular, the history and archaeology of the Celtic Kingdom of Noricum is explored in detail, as this polity came to control most of the Eastern Alps as well as the Salzach River Valley.

Article Outline

- Salzburg Prehistory

- Upper Paleolithic (Late Stone Age) 50,000-12,000 years ago

- First settlement (40,000 BC) by early modern humans (Cro-Magnons)

- Aurignacian culture

- End of the last ice age (12,000 BC)

- Development of agriculture (4,000 BC) and villages

- Bronze Age in Central Europe (2,300 BC – 800 BC)

- Upper Paleolithic (Late Stone Age) 50,000-12,000 years ago

- The Hallstatt Culture (1,200-475 BC)

- Late Hallstatt (C/D periods, 800-475)

- Discovery of Iron (Iron Age) c. 800

- Late Hallstatt (C/D periods, 800-475)

- La Tène Culture and Celtic Salzburg (450-16 BC)

- Emergence of the Celts

- Invasion/spread throughout Europe

- Celtic culture/society

- Celtic fortified settlements (oppida) in Salzburg and Eastern Alps

- The Veneti

- The Kingdom of Noricum (183-16 BC)

- Early contact with Rome

- The Cimbrian War

- Noricum and the Late Roman Republic

- Salzburg and Noricum

- Annexation by Rome

I. Salzburg Prehistory

Salzburg State, the region surrounding the city, has been settled by humans for tens of thousands of years. A cave in the region has human remains dating back to 40,000 BC, a time when the Salzach river valley was dominated by glaciers. It was at this time European early modern humans (Cro-Magnons)[1] were displacing Neanderthals in central Europe. Members of the Aurignacian archaeological culture, these stone-age people made tools out of bones and antlers. It is impossible to know what compelled people to move into an area dominated by towering glaciers and mountains, but the earliest humans were hunters who may have been following herds of reindeer through the narrow mountain passes.

Farming would not begin in the region for another 36 centuries. New people came to Austria c. 10,000 BC, and started farming in small settlements around 4,000 BC. Using stone and wooden tools, these first farmers cleared forests and plowed their land. Other evidence suggests grain cultivation and land clearance in the Alpine foothills as early as the 5,000s BC. A single family during this Neolithic period (starting c. 4,500 BC in Austria) required 3 hectares of farmland to survive. Because of the primitive tools available, farming was excruciatingly difficult. The wheel was only introduced in the 2000s BC, at the start of the Bronze Age (c. 2,300 BC).

After a period in which copper metallurgy was dominant, the Bronze Age allowed for more sophisticated social stratification, the development of a primitive currency (rib ingots), and mining. The site at Mitterberg became the center of Bronze Age Metallurgy in central Europe, and here copper mining peaked in the 1000s BC. Copper was combined with tin to make bronze. Because tin was a much more scarce resource, it had to be imported from the Ore Mountains, today on the border between Germany and the Czech Republic.

During this period, the rich salt deposits in Salzburg state were discovered, probably by hunters who observed reindeer making use of salt-licks. Created by the tectonic movements that forged the Alps in the Jurassic period, these salt veins stretched from the Tyrol region all the way to modern Vienna. Regular salt mining and extraction began at Dürnberg by the late Bronze Age (c. 500 BC). The salt and bronze mines, controlled by powerful local princes and chieftains, became important centers of production and manufacture for the whole of Europe. The region served as a crossroads for trade, with Baltic amber and Italian and Greek vessels being traded for salt, bronze, and copper.

By the end of the Bronze Age, the region around modern Salzburg was a continental trade hub.

II. The Hallstatt Culture

Discovered human remains provide insight into life during this period. The middle Bronze Age (1500-1200 BC) corresponds with the Tumulus culture, during which bodies were covered in mounds. During the late Bronze Age (1200-800 BC), the Urnfield culture predominated, and bodies were cremated and buried in urns. Bronze swords were thrown in swamps, and sacrifices made as tributes to unknown gods.

The Late Bronze Age saw the emergence of the Hallstatt culture (the period 1200-800 BC corresponding to the Hallstat A/B phase). This culture was first identified at the town of Hallstatt in Austria, directly 20 miles southeast of Salzburg, and emerged out of the Urnfield. The famous Iron Age Celts that would come to dominate Europe are believed to have originated out of the Hallstatt culture, who are traditionally regarded as Proto-Celts (or even fully Celtic in the later Hallstatt phases, C/D)[2].

Originating in the Salzkammergut, the region including Salzburg and Hallstatt, the Hallstatt culture spread to multiple independent villages across central Europe. Society was controlled by a wealthy elite who regulated access to raw materials and trade. The upper class was buried in elaborate grave mounds, often with chariots (horse wagons) that were a symbol of their authority. Weapons and jewelry featured abstract geometric designs, though luxury goods continued to be imported from the Greek Mediterranean. It is possible that a shared Proto-Celtic language developed among these early Hallstatt people.

In the Salzburg region, chiefs continued to maintain their power by controlling salt mines, continuing a pattern from the pre-Hallstat era. The Hallstatt type site, located in the namesake town south of Salzburg, has yielded over 1,300 graves buried between 1200 and 500 BC, and surrounding ancient mines have preserved textiles, tools, and even food remains from this period. This site was likely the dominant settlement among the western Hallstatt culture, though magnificent burial mounds for individual chieftains have been discovered elsewhere.

The discovery of iron in the 8th century revolutionized Hallstatt society. During the Hallstatt C Period (800-600 BC, the early Iron Age) elaborate hilltop settlements[3] were created as a more advanced material culture developed. As society moved into the last phase of Hallstatt (Hallstatt D, 600-475 BC), these hilltop fortifications become complex centers of trade and manufacturing. By the classical period, these fortified hill settlements were important economic centers to Celtic society, at least in Britain. However, there was little direct continuity between Hallstatt hill sites and later Celtic ones.

In the 7th century, small Hallstatt villages were formed in the hills around modern Salzburg, and also likely occupied Rainberg hill (Stadtberge). Evidence suggests that this site had been occupied long before the Hallstatt, as early as the Neolithic (4500 BC).

III. La Tène Culture and Celtic Salzburg

In a brief 50-year period, Hallstatt society suffered a period of disruption (500-450 BC), and Hallstatt hillforts were abandoned all over Western Europe. Archaeologists are unsure if this event was caused by invaders or internal strife, but a new material culture emerged- the La Tène. Named after a type site found in Switzerland, the La Tène culture lasted from 450 BC to the start of the first century. The La Tène culture can essentially be regarded as the material culture of the Celts. For almost 500 years, the La Tène was the dominant iron-age material culture in Western Europe. Emerging in the northwest fringe of the Hallstatt, between the valleys of the Marne and Moselle rivers (eastern France, SW Germany), La Tène culture would spread (450-200 BC) with the Celts across the European continent from Spain to Anatolia.

Celts (called Gauls by the Romans)[4] entered the written record as they invaded the Classical Mediterranean world. As early as the 5th century BC, Celts had entered the Po Valley and were thus established in Northern Italy. In 387, Gauls sacked the city of Rome, striking a serious blow to the early Roman Republic. In 279 Celtic tribes poured into the Balkans, Macedonia and Greece, going so far as to sack the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. Greek authors commented on the ferocity of their opponents and the vicious blows struck by Celtic longswords, which forced Greek hoplites to resort to skirmishing tactics.

The Celts were never unified politically, but operated as tribes and shifting tribal coalitions. Usually governed by kings, though often by tribal oligarchies, Celtic societies were dominated by a warrior aristocracy. In mainland Europe, some Celts lived in fortified cities (called oppida). In the La Tène period, the Celts had complex trade relationships with Mediterranean cultures, namely the Romans and the Greeks. Mediterranean art strongly influenced the development of native Celtic metalwork.

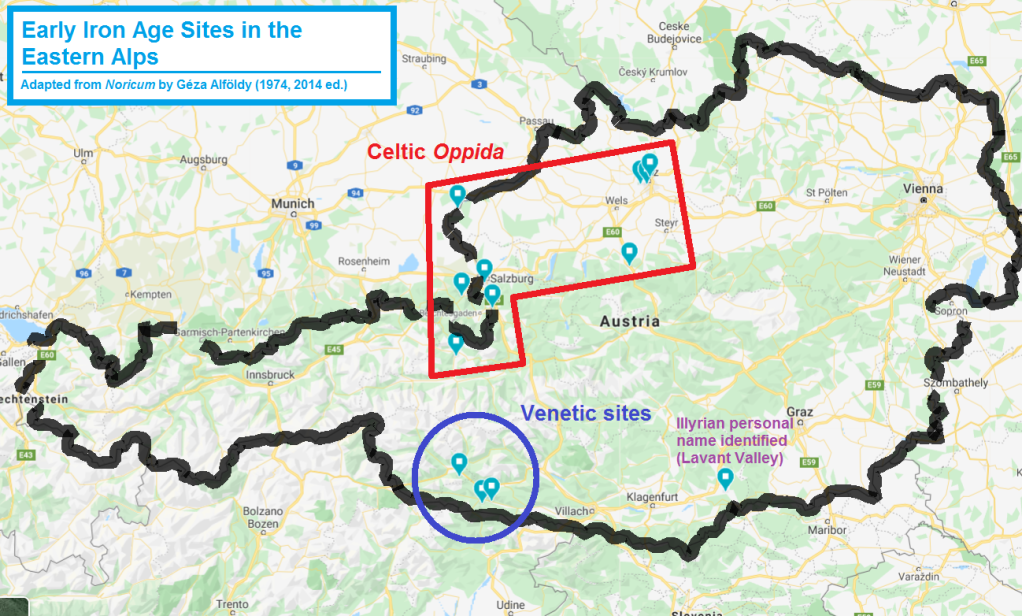

By 350, the La Tene Celts were firmly established in the northern part of Salzburg state, as well as Upper and Lower Austria. Many Celtic archaeological remains have been concentrated in Salzburg and the city of Durrnberg in the middle of the Salzach valley. A number of oppida have been identified in modern Salzburg State and Upper Austria, including at Saalfeldern-Biberg (upper Salzach valley), Karlstein and Durrnberg (Hallein) as centers of salt mining. The Duurnberg site in particular has yielded many artifacts. Within modern Salzburg’s city limits, Rainberg hill was an oppidum which evolved into a nucleus of proto-Salzburg.

IV. The Veneti

At first, the Celts were not the only people in the early Iron Age (800-600 BC) Alpine regions. The Veneti and Illyrians[5] were non-Celtic peoples who were present in the Eastern Alpine region during this time. The Veneti were an Italic culture that flourished independently of the Celts only briefly, and were subsumed in waves of Celtic migration at the end of the Hallstatt. The extent to which the Veneti persisted or were absorbed completely by the Celts as a people cannot be entirely answered, but there is firm evidence for their origin as a non-Celtic culture. The Veneti chiefly flourished in northeastern Italy, but at least two surviving inscriptions of the Venetic language survive that attest to their presence in the Eastern Alps: (1) personal names carved on a crag near the city of Würmlach (80 miles south of Salzburg), and (2) a set of bronze-fittings in wooden box in the nearby hamlet of Gurina/Dellach. The Veneti here were established in the upper Gail valley, today in the Austrian state of Carinthia (Kärnten).

V. The Kingdom of Noricum

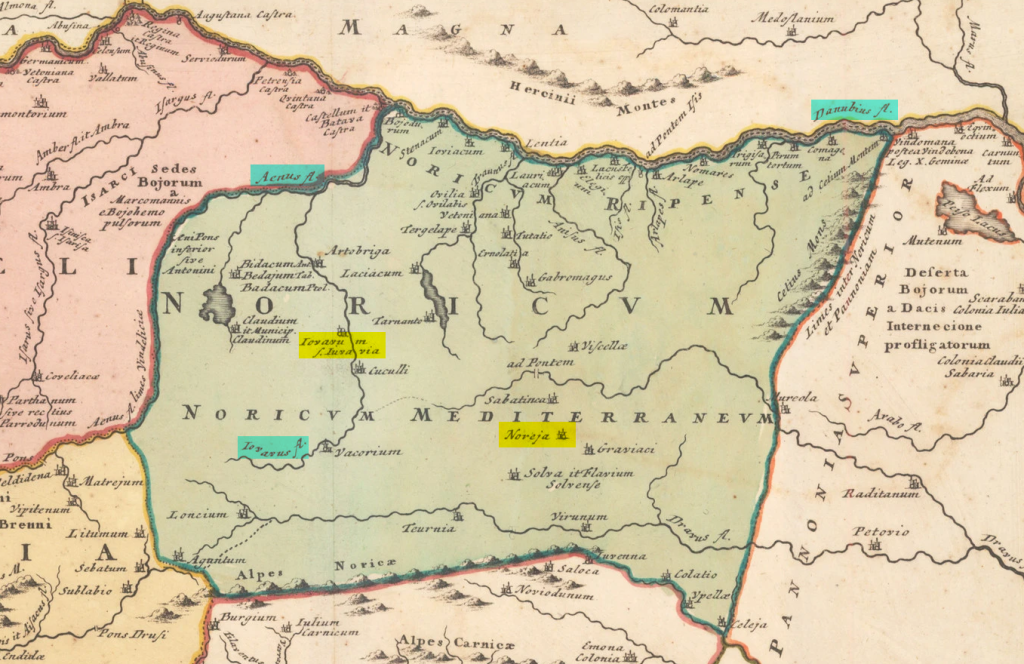

Before 200 BC, a group of Celts and the remnants of the Veneti/Illyrians coalesced as two tribal groups- the Taurisci and the Norici.[6] These two tribes dominated the Eastern Alps and the area south of the Danube. Eventually, the groups merged, becoming a single confederation, though they retained separate identifies into the first century AD. At times, ancient authors may have referred to both simply as Norici.

While the Norici did not live directly in modern Salzburg, the Celts who did (the Ambisontes) pledged their allegiance and eventually became part of the Norican Kingdom. Because relatively little is known about the Ambisontes (see below), the history of pre-Roman Salzburg is best understood through the history of the Kingdom of Noricum.

V-1. Early Contact with Rome

Sometime in the 3rd century BC, the Norici made contact with the Romans, likely when the Roman Republic was conquering Celts living in the Po Valley.

Livy, the greatest Roman historian, wrote about a bizarre incident that set the tone for the future relationship between these peoples (Book 39 of Ad Urbe Condita). In the year 186 BC, Norican people crossed into the Po valley, entering into Roman territory, wandering and peacefully founding a settlement (later called Aquileia). It seems that these Gauls may have believed that the Romans actually did not intend to occupy this region.

Alarmed that an unknown group could just wander in and form a village, the Romans sent delegates to the Norican leadership, sending a praetor (senior Roman official) across the Alps to negotiate. The Norici responded that they had no idea why the group left and that they had done so without permission. It seems that this incident was resolved without bloodshed.

This episode is illustrative of the relationship that would be established between the Norici, later the Kingdom of Noricum (after 183)[7] and the Romans. The Romans believed all Gauls to be barbarians, and the sack of their city in 387 left the Roman psyche permanently fixed on violently removing any perceived threats from their Gallic neighbors. The fact that this incident was resolved peaceably shows a level of cooperation and trust built between the Romans and the Norici that was exceptional.

In contrast to their Celtic neighbors, most of whom would be violently conquered, the Norici built strong ties of friendship with their Roman neighbors In 178, Noric soldiers led by a certain Catmelus assisted the Romans in subjugating the tribes of Istria. Livy refers to the king of Noricum, Cincibilis (regulus trans Alpes, the king beyond the Alps). Catmelus (possibly the king’s brother), evidently had a working relationship with Roman senators, a powerful leg-up in negotiations. The king even offered help to the Romans in their war with Macedonia (169 BC).

In assisting her powerful southern neighbor, the kings of Noricum received means to consolidate their own power at home and build strength in the region. The Norici also benefited from Roman trade, with close mercantile relations beginning during mid second-century BC, evidenced by an influx of Roman currency at the time. A gold mine established in this period bolstered the success of the kingdom. Roman traders and merchants set up shop in Noricum in order to conduct business, and Latin permeated the region. One merchant family in particular, the Barbii of Aquileia, were the foremost traders. Inscriptions testify to their presence and a bronze statue has been discovered dedicated by the family.

It can only be wondered what the Norici thought to themselves as Rome conquered all of Macedonia, Greece, then Syria, much of Spain, the Levant and the African coast. Maybe they were amazed to be allied to such ferocious people, and doubtless that amazement was coupled with fear. After the middle of the 2nd century BC, the internal dynamics of the Roman Republic became increasingly chaotic, with political disputes turning into bloodshed. As the ambitions of Roman politicians turned outwards against barbarians, the Norici must have been highly attentive in maintaining good relations.

V-2. The Cimbrian War

Around 120 BC, flooding in the Jutland peninsula (modern Denmark) forced three Germanic tribes south- the Cimbri, Teutones, and Ambrones. Migrating into central Europe, they allied with the Celtic Tigurini, forming an enormous new tribal coalition. With many tens of thousands of warriors (possibly as high as 200,000), they moved southward to settle in new lands. This was the beginning of a long period of Germanic migrations, and over the next 500 years Germanic peoples would absorb, displace, or destroy much of Celtic central Europe.

According to Livy, the invading tribes crossed the Danube in 113 and entered the territory of the Kingdom of Noricum (specifically, the lands of the Taurisci, who still were still a separate but related group). The Norici/Taurisci called on their Roman allies, who sent an army of 30,000 led by the consul Papirius Carbo. The Romans, their Celtic allies and the Germanic coalition met just outside the capital city of Noreia. A ferocious battle ensued that ended in decisive defeat for the Romans and the Celts. The Romans lost 20,000 men, with an unknown number of Celtic dead. The fate of Noreia (possibly modern Magdalensberg, Austria) remains unknown, though the city may have been sacked by the victors.

In the long conflict (113-101 BC), the Romans suffered a number of terrible defeats at the hands of the Cimbri, Teutones and their allies. This war (the Cimbrian War) provided the greatest threat to Roman power since the war with Carthage, and would see the annihilation of multiple legions.

Much of this conflict took place north of the Alps. Terrible destruction must have been wrought on the farms, villages, and oppida of the Norici and Taurisci, but no literary evidence attests to their suffering. After prolonged crisis, newly re-elected consul Gaius Marius destroyed the Cimbri and Teutones in two decisive battles, only after the defeat of four other Roman armies. Through it all, it seems that the king of Noricum remained firm allies of Rome.

V-3. Noricum and the last years of the Roman Republic

In 60 BC, an army of the tribe of Boii (Celts from modern-day Slovakia) besieged Noreia. Failing to capture the city, they were driven off by the Noricii and moved westward. The Boii had been in conflict with the Dacians (people from modern Romania), and it is likely they were forced from their homeland and sought to settle across the Danube. Archaeological evidence shows evidence of a first-century BC siege near Magdalensberg.

References to the Norican conflict with the Boii come from Julius Caesar’s writings on the Gallic Wars (Commentarii de Bello Gallico), a description of his campaigns in Gaul from 58-50 BC.

Caesar, at the time simply a prominent Roman politician, was given control of three Roman provinces, including a strip of Gaul north of the Alps. Over the course of eight years, he would completely bring the whole of Gaul (modern-day France) under Roman rule, conquering millions of Celts in a series of military victories and treaties with tribes.

In 58 BC, none of this was certain, and Caesar appeared to be another official in a long line of governors (proconsuls) seeking to extend Roman influence in the region. After their defeat, the Boii moved to modern-day Switzerland and allied with the Helvetii, another Celtic tribe. In order to counter this alliance, the Norican king Voccio sent his sister to marry the leader of the Suebi, Ariovistus. The Suebi were a powerful Germanic tribe seeking to extend their influence in Gaul, and Ariovistus led numerous incursions across the Rhine. Raids against a different Roman-allied tribe brought Caesar north, and the Germans were defeated.

Although Voccio had backed the wrong horse, he remained in Rome’s good graces. Caesar even sent Roman engineers to repair Noreia, which was still recovering from the siege.

Within eight years Gaul was conquered by the Romans, largely ending independent Celtic Europe[8]. Elements of Celtic/Gallic culture still thrived under Roman rule, over the centuries developing into a new Gallo-Roman hybrid. However, the Druids, priests of the old Celtic religion, were wiped out as a class after preaching resistance. In Roman Gaul, as well as Noricum, elites increasingly adopted Latin and manners of Roman culture in order to successfully engage in trade and compete for political resources.

Only by allying Rome had the Kingdom of Noricum preserved its independence. Keeping his constancy with Caesar, king Voccio provided him with 300 cavalry during the next Roman civil war, in which Caesar defeated his rival Pompey (49-45 BC). Shortly thereafter, Caesar was assassinated, and Rome quickly descended back into bloodshed.

In these last decades of the Roman Republic (44-27 BC), Noricum took the opportunity to expand. With the collapse of the Boii, who had been decisively defeated by Caesar, the Noricii were able to expand far east as Lake Balaton (modern Hungary). To the north, the kingdom controlled all territory until reaching the Danube, and was bounded in the west by the Inn River. This was the last period of Norican expansion, and the kingdom was at the height of its power.

V-4. Salzburg, the Ambisontes and Noricum

The Kingdom of Noricum was not a centralized state, in fact the king ruled over multiple smaller tribes who pledged to him their loyalty. Among these was the Ambisontes, who lived in the Salzach valley and likely controlled the Rainberg Hill oppidum within modern Salzburg. They were said to have migrated to the valley in the 4th century BC under a leader named Segovesus, coming from an older tribe in Gaul (the Bituriges). Settling on either side of the Salzach River, the Ambisontes were likely the first La Tène Celts in the valley, and may have controlled all of the oppida sites identified earlier (Saalfeldern-Biberg, Karlstein and Durrnberg). They were certainly involved in operating the (already) ancient salt mines. By the late first century, the Ambisontes were understood by the Romans to be a tribe controlled by the Noricum.

V-5. Annexation by Rome

Although the Kingdom of Noricum controlled the eastern Alps, that control was not total, and the Alps in general were notoriously lawless, making travel difficult between Italy and the trans-Alpine provinces. Many of the Celtic tribes operating in the Alps were outside the control of either Rome or Noricum. Additionally, Dalmatia, Pannonia, and the northern Balkans contained wild territory.

In 31 BC, the final civil war of the Roman Republic ended and Rome became a dictatorship. In 17 BC the first emperor, Augustus, began a great northern offensive that sought to finally bring the Alps, Pannonia, and the northern Balkans under Roman domination. This giant campaign finally ended the autonomy of the Kingdom of Noricum, which (largely) peacefully submitted into becoming a Roman province. The Eastern Alps were portioned into three provinces- Raetia, Noricum (which contained most of the former kingdom), and Pannonia Superior.

The Noricii had set themselves up for trouble while plans for a Roman campaign were still being drawn. Despite centuries of loyalty to Rome, in 16 BC the Noricii attacked the Istrians in battle, who were at that time Roman provincials. Although this was a small affair, probably conducted by a subordinate tribe acting outside of the king’s wishes, it provided enough of a pretext for Rome to take complete control of Noricum as part of the northern offensive.

Although a great blow to the Norican royal family[9], most of the Noricii found direct rule tolerable. For generations the elite of Noricum had adopted aspects of Roman culture and were likely to continue to prosper under Roman occupation. Rome could no longer tolerate the loosely-organized kingdom on her border, but people continued living there much as they had for centuries.

Not all of the kingdom’s tribes submitted peacefully however. The Ambisontes, the tribe of the Salzach valley, attacked the Roman invaders, revolting alongside two other non-Norican tribes (the Raeti and Vindelici). A victory monument discovered near Monaco attests to their defeat and subjugation. What did this mean for the Salzach valley, and the oppidum at Rainberg Hill?

At the Taxenbach Strait, a section of the Salzach river, a fortified hill has been discovered that shows signs of warfare. La Tene artifacts were discovered mixed with sword blades, scabbards, and shield bosses. This could be evidence of the Roman conquest. [10]

Almost nothing is written about the battles that happened there, except a few lines written by two later authors. Strabo records “Tiberius and his brother Drusus stopped all of them…by means of a single summer-campaign.” Tiberius would later become Rome’s second emperor. Appian, more than a century later, indicates that he was unable to find any information pertaining to the Alpine campaign. It is likely that the overall tranquility of the Norican conquest made for very little contemporary writing on the subject.

In 10 BC, a monument in Magdalensberg was set up by leading Norican tribes. The monument was dedicated to the women of the imperial family, and included praise of the emperor’s wife Livia. The Celtic tribes of Noricum had definitely become loyal subjects of the Roman Empire.

Shortly after the Roman takeover, settlements around Rainberg hill coalesced into a single settlement, called Juvavum. After centuries had passed, this city would come to be known as Salzburg. For an unimaginably vast period of time, humans had hunted, fished and farmed along the Salzach River. Since the advent of farming, people lived on Rainberg hill, later the Hallstatt people resided there, then the Celts. Having considered the earliest people who resided in the region, next we will look at Juvavum under the Romans, who lived in the city for some 500 years.

SOURCES

- Almost all information on stone-age and Bronze Age Salzburg came from the Keltenmuseum in Hallein, Austria. This museum has incredible artifacts from both the Celts and their precursors, as well as exhibits on salt-mining and later eras in Austrian history. I am very fortunate to have visited this museum in 2018 and have used photographs from exhibits throughout the article. It is a necessary stop for anyone visiting Salzburg who is interested in the history of the region. I would like to emphasize that I have no affiliation with the museum, and any research claims I have made in error are entirely my own.

- For the Hallstatt, La Tene cultures as well as overall continental Celtic history:

- The Ancient Celts by Barry Cunliffe (1997)

- The Celts: A Chronological History by Daithi O Hogain (2002)

- Celts and the Classical Word by David Rankin (1987, 2003 ed.)

- The Celtic Encyclopedia by Harry Mountain (1997) for information on the Ambisontes

- The foundational source for anything regarding the Kingdom of Noricum comes from Géza Alföldy’s Noricum (1974, 2014 ed.) This monumental work covers the entire ancient history of the region from 400 BC to the end of Roman rule in 600 AD, drawing on both archaeology and literary resources.

- Also very helpful was by Alois Streicher & Phillip Kriechammer’s Die Geschichte Noricums(the History of Noricum) (2012), a summary document of Alföldy’s Noricum that considers other recent resources and provides primary source texts from Livy and inscriptions.

NOTES

[1] European early modern humans (EEMH) were the first anatomically modern humans in Europe, appearing as early as 48,000 years ago. Previously called Cro-Magnons, the Aurignacian (43,000-28,000 years ago) was only one material culture associated with their unimaginably long history. A period of de-glaciation (15-13,000 BP), and then the final end of the last ice age (12,000 BP) led to an influx of new peoples into Europe, merging with the EEMH and forming the basis of pre-Indo-European (Neolithic) Europe.

[2] The relationship between the Hallstatt people and the Celts is a complicated one, though the La Tène material culture is usually seen as the material culture of the Celts of classical antiquity. It is important to remember that material cultures are defined by archaeologists and do not always meet up neatly with tribes, cultures, or societies described by ancient authors. Additionally, many archaeologists (and anthropologists) are hesitant to link material cultures with historical groups, seeing such associations as counter to the science of archaeology.

[3] The term ”oppida” seems reserved for La Tène Celts

[4] “Celt” comes from the word Keltoi, likely a word developed by the Greeks of Massilia in the modern south of France. It apparently described a specific tribe, but came to be applied broadly. The Romans preferred the name of “Gauls” (possibly from a tribe, the Galii) but sometimes used the term Celtae. It is notable that neither of these terms were applied to the ancient Britons. In his writings, Caesar noted that the Gauls themselves used the term “Celt.”

[5] Illyrians are an ancient people who lived principally in the Balkans. In archaeology, there has been a great deal of debate about who-or-what defines an Illyrian (see p.15 in Alfody’s Noricum). Alfody, writing in 1974, noted that there is scarce attestation of Illyrian presence in the Eastern Alps. I was unable to determine today’s academic consensus on the extent of Illyrian culture or society in or north of the Alps.

[6] These two confederations were identified by the ancient geographer Strabo (63 BC-24 AD) and Pliny the Elder (23-29 AD), suggesting the persistence of these tribes into the first century AD

[7] Livy does not refer to any king when discussing the earliest contact between the Norici and Rome in the 186 BC incident, but does when writing about the 178 BC Noric troop contingent led under Catmelus.

[8] With the exception of the Britons, though they would eventually be conquered during the reign of Claudius (beginning in 43 AD).

[9] I was unable to find any information pertaining to the fate of the King or his descendants.

[10] This was information provided in a plaque in the Keltenmuseum.