By N.

Classical Athens is a common subject of study. Rising to prominence among the Greek city states, Athens exerted cultural and economic control throughout the Greek world. Home to many of the most famous figures of Ancient history, the classical city-state produced Pericles, Socrates, Plato and other famous individuals. However, after Athen’s defeat during the Peloponneisan War (431-404 BC), the city’s political history is often overlooked. Although no longer the center of a regional empire, Athens was still was an economic and cultural center of Greece. The following is a brief overview of Athenian political life after 404 and before the entry of Rome into the eastern Mediterranean.

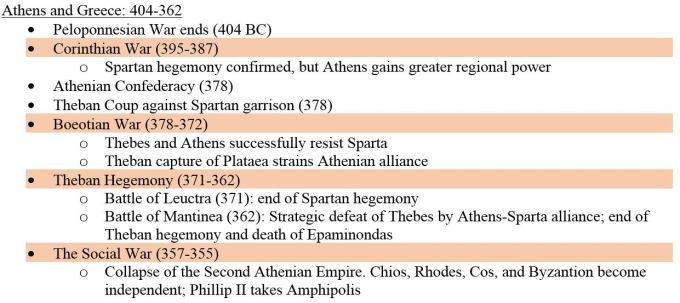

Athens and Greece- from 404 BC to the Macedonian Invasion (356)

The Peloponnesian War resulted in the loss of Athen’s empire, and Sparta became the chief power (hegemon) among the Greek cities. For the next 50 years, Athens would struggle to regain her former political influence, bringing the city-state again into conflict with her arch-rival Sparta. After further conflict with a new Theban hegemony (362), all of Greece became vulnerable to a rising northern power.

Immediately after the war, Athens was forced into becoming a “subject-ally” of Sparta and had its democracy abolished. Sparta was always unhappy with Athenian democracy and sought to replace it with a more familiar form of government. The Spartan-approved Thirty Tyrants ruled Athens as oligarchs, though their reign was short lived- Athens was again a democracy by 403.

Athens slowly began to challenge Spartan hegemony over Greece, as the Spartans were alienating the other Greek states with their rule. Although the Spartans had fought Athens for the supposed liberation of all Greek states, the rule they imposed after 404 did not win them much support. Conflict broke in the Corinthian War (395-386), where Athens joined a coalition against Sparta with Corinth, Thebes, and Argos. Importantly, Athens had the support of the Persian Empire, Sparta’s former ally (throughout the Peloponneisan War, the Persian empire had provided Sparta with gold and naval support). At the battle of Cnidus (394) a Persian fleet defeated the Spartans under the command of the Athenian admiral Conon. After peace was made, Athens was able to rebuild her regional power in a new Athenian Confederacy in 378.

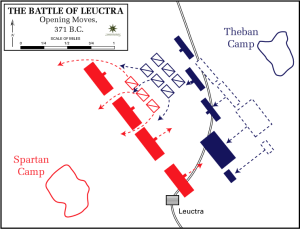

Thebes joined this Athenian confederacy, but soon proved to be too powerful for Athens to dominate easily. Nevertheless, further warfare diminished Spartan power, and at Leuctra in 371 Thebes became the leading power in Greece.

Although Athens shared in the Theban victory, she in turn was alienated by that city’s new influence. This forced the city into rapprochement with her formal rival. Thebes was defeated by an unlikely Sparta-Athens alliance in 362. In the power vacuum that followed, Athens tried to establish its empire, but her attempts to control the city of Amphipolis proved too much. Former Athenian allies rose up in revolt against Athens in the Social War (357-355), thwarting the recreation of Athenian dominance.

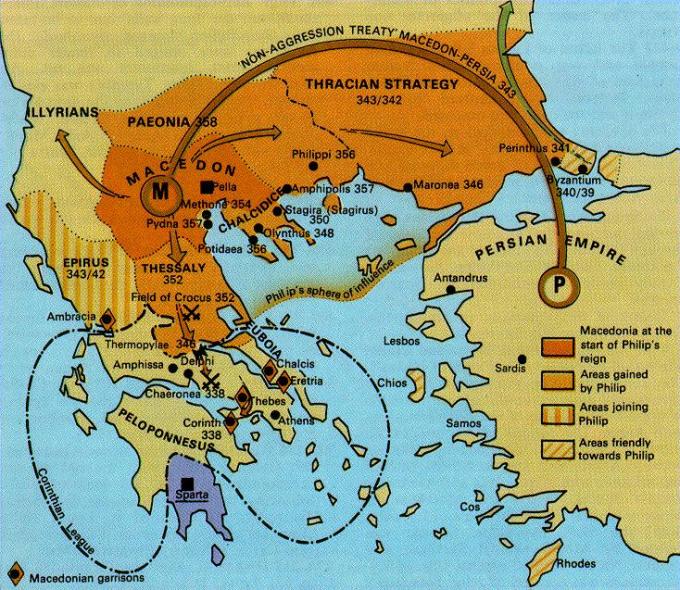

Macedonian control: Phillip and Alexander

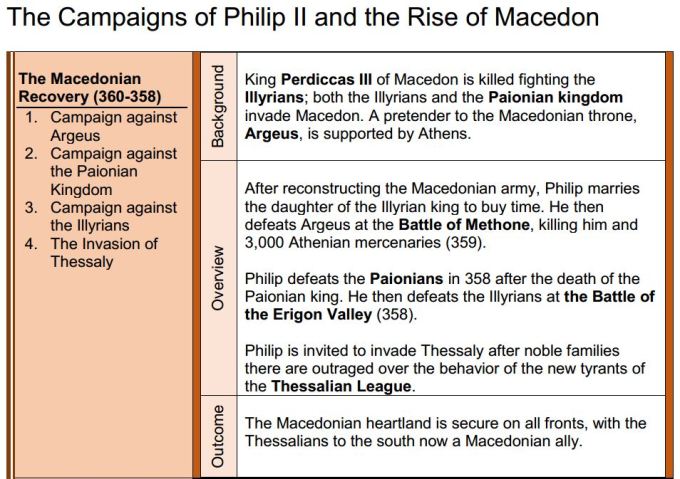

A century of fighting between the Greek city states was noted keenly by the Macedonian kingdom to the north. Greek weakness allowed for the Macedonian conquest of Greece under Philip II, who rapidly expanded Macedon’s power after his accession in 360. Philip’s initial campaigns in northern Greece brought him into conflict with Athens, who was unable to intervene decisively because of the ongoing Social War. Philip ultimately defeated an alliance of Greek states at the Battle of Chaeronea (338).

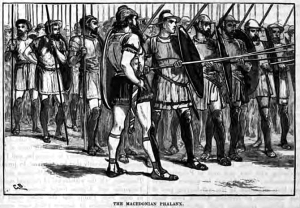

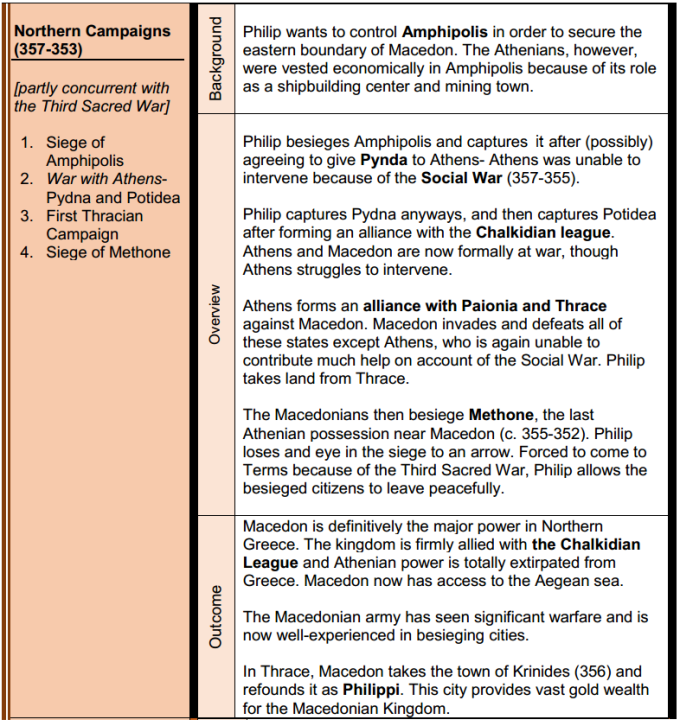

Phillip had made a number of improvements to the traditional Greek hoplite phalanx formation in armies that gave the Macedonians battlefield advantage. He introduced the sarissa, a 20 ft pike carried by his forces that outranged the usual hoplite spears. Athens was forced into the Corinthian League, which reduced Athens to a Macedonian client-state. All Greek cities were forced into the League except for those on Crete and Sparta. Sparta had become a second-rate power over the last century, though it was still able to maintain its own local autonomy in the face of Macedonian hegemony.

When Phillip died in 336, Athens and Thebes rebelled. Phillip’s son and successor Alexander the Great destroyed Thebes entirely and sold its population of 30,000 into slavery. Athens re-submitted shortly after and was spared serious repercussions for its rebellion. Alexander took the Macedonian army on to conquer the Persian Empire and spread Macedonian control all the way to India.

Athens and the Wars of the Diadochi (322-275)

The death of Alexander in 323 began a very tumultuous 50-year period in the history of Athens and the Greek world. The giant Macedonian Empire, stretching from Macedon in northern Greece all the way to the Indus river valley, would soon begin to fragment as the competing successor generals (diadochi) fought each other for control. Athens would pass through the hands of a number of diadochi before finally before finding as a client state of the Antigonid kings.

When Alexander died, Athens rebelled against Macedon for a second time. In the Lamian war (323-322), Athens, the Aetolian league and other Greek states fought against Macedon again. The Greek allies were able to defeat the Macedonians at Thermopylae (323) under Antipater, who was the regent of Macedonian Greece. Antipater was under Perdiccas, the succeeding general who had been made regent over the whole Macedonian empire.

The naval defeat of the Athenians at Amorgos and their failure at Crannon (322) forced the allies to submit to Antipater. Athens had been given generous terms after their defeats by Phillip and Alexander, but Antipater was fed up with Athenian trouble making. He forced Athens to give up the island of Samos and installed the tyrant Phokion. Piraeus, the Athenian port city, had a permanent garrison of Macedonian soldiers installed, bringing Athens tightly under control. The great Athenian anti-Macedonian orator Demosthenes killed himself in order to avoid capture.

As political intrigue spread quickly amongst the Macedonians, Antipater allied himself with Antigonus, another general who had been made regent in Asia minor. Antipater, Antigonus, and Ptolemy (the Satrap of Egypt) rebelled against Perdiccas with the forces under their control. Perdiccas was killed and Antipater made himself the new regent of the whole Macedonian Empire. Arriving in Macedon, however, Antipater fell ill and died in 320. With the death of Antipater, the other diadochi began to seize control of different portions of the Empire for themselves.

Cassander, another general, seized control of the original Macedonian homeland and Greece. Cassander put his own man Demetrius of Phalerum in charge of Athens. Cassander entered into an alliance with Ptolemy (now Pharaoh of Egypt), Lysander (who held Thrace), and Seleucus (who took control of much Asian territory) against Antigonus, who held much of Asia and Asia minor. Although Antigonus was facing off against most of the other diadochi, he held an extremely large amount of resources and would prove capable in defending his domains.

Athens, although under Cassander, recieved envoys from the other diadochi, acknowledging its preeminent role in the Hellenistic world . Seleucus sent tigers as a gift; Antigonus managed to develop a faction loyal to himself in Athenian politics and even had an Athenian unit under his command.

Antigonus’s conflict with Seleucus proved most disastrous. In the Babylonian War (311-309) Antigonus lost most of his Asian territory to the Seleucid Empire. Shifting focus westward, in 307 Antigonus challenged Cassander’s control of Greece by sending his son, Demetrius (later called Poliorcetes “the besieger”), to invade with 250 ships. Demetrius successfully took Athens. Before his arrival, the pro-Antigonid faction had risen up in his favor, forcing Demetrius of Phalerum to flee to Ptolemy in Egypt. Demetrius promised a full return of democracy to Athens. The Athenians, estatic, declared their support for Antigonus as King and savior of Athens. For a city historically hostile to autocracy, these sentiments were unprecedented. George Grote, in his History of Greece (Volume XII, pg. 376-377) writes:

In reviewing such degrading proceedings we must recollect that thirty-one years had now elapsed since the battle of Chaeroneia, and that during all this time the Athenians had been under the practical ascendancy and constantly augmenting pressure of foreign potentates….By…Demetrius Phalereus and the other leading statesmen of this long period submission to Macedonia had been inculcated as a virtue while the recollection of the dignity grandeur of old autonomous Athens had been effaced or denounced as a mischievous dream…During this thirty years…a new generation of Athenians had grown up accustomed to an altered phase of political existence…

The sentiment of political self-reliance and autonomy had fled; the conception of a citizen military force, furnished by confederate and co-operating cities, had been superseded by the spectacle of vast standing armies, organized by the heirs of Alexander and of his traditions.

Although Demetrius promised democracy in Athens, the decisions made by the Athenian assembly could be ignored or accepted by him or his father. Independent Athens was gone, and yet the citizens had embraced this joyously.

Although Demetrius had taken Attica, most Macedonian territory remained in the hands of Cassander. In order to increase his legitimacy, Cassander married the half-sister of Alexander. He would later have Alexander’s wife Roxana and only child (Alexander IV) murdered.

Although unable to drive out Cassander, the Antigonids had further successes- Demetrius defeated Menelaus, the brother of Ptolemy, in a gigantic naval battle that destroyed the Ptolemaic navy (Salamis, 306 BC). Demetrius besieged Rhodes in 305, and was forced to retreat, leaving behind gargantuan siege-craft around that city. The Rhodians would later put these to use in building their Colossus statue.

Demetrius and Antigonus faced off against the forces of Lysimachus, Cassander, and Seleucus at the Battle of Ipsus (301). The fate of Greece and the new hellenistic world order was determined in this gigantic battle.

The allied diadochi brought over 400 war elephants, giving them the advantage. Antigonus was defeated and killed during the battle, forcing Demetrius to flee back to his Greek domains. Although Athens had embraced Demetrius in 307, they now turned his back on him and refused him entry into Attica. His reign, apparently, had proved more cruel then they had anticipated. Demetrius was left with only his navy, and was unable to compel the Athenians with force.

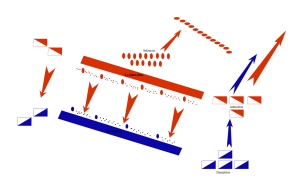

With the defeat of Demetrius, democratic Athens moved to strengthen its own autonomy. Another tyrant soon appeared however- Lachares. Lachares was a mysterious figure who was able to wrest control of Athens with the help of Cassander. In order to pay his forces to control the city, Lachares melted down and sold all of the gold and silver ornaments of the Parthenon. In response to the new Athenian alliance with Cassander, Demetrius began raiding the city’s trade partners.

When Cassander died in Macedon (297), war broke out between his two children. This allowed Demetrius to invade Macedon and take over the kingdom by allying himself to one of the sons, and later murdering him. Before he took the Macedonian heartland, Demetrius was able to conquer Athens in 295, despite Ptolemy having sent a fleet to aid Lachares against Demetrius. By the end of 294, Demetrius now controlled all of the territory formerly held by Phillip, making himself the King of Macedon. Lysimachus continued to hold Thrace, Seleucus held all of the empire’s Asian territories, and Ptolemy continued to rule as Pharaoh in Egypt.

After taking Athens, Demetrius again allowed democracy to return to Athens, though again the city was ultimately dependent on his authority.

Demetrius was never secure in Macedonia. For the rest of his life, he found himself at war with the King of Epirus, Pyyrhus, and Lysimachus in Thrace. He raised heavy taxes in Greece to pay for these wars which made him extremely unpopular in Athens. Demetrius was eventually captured by Seleucus and he died in captivity in 283.

After Demetrius was captured, the throne of Macedon went to Lysimachus, who had extended his control now over Thrace, Macedon, and Greece. Shortly after Lysimachus was killed at the battle of Corupedium in 281 fighting his old ally Seleucus. At the battle was Ptolemy Keraunos, the eldest son of the Egyptian Pharaoh, serving as an officer under Seleucus. Seleucus wished to extend his massive Asian empire into Macedon, but Ptolemy Keraunos saw this as an opportunity to take Macedon for himself. After they successfully defeated Lysimachus, Ptolemy murdered Seleucus and seized the throne of Macedon for himself. Control of the Seleucid Empire would pass to the son of Seleucus, Antiochus.

Macedonian control: The Antigonid Dynasty

The collapse of the kingdom of Lysimachus in Thrace brought in a new invader from the north- the Celts. A giant mass of 90,000 Celtic warriors pushed through the southern Balkans in 281 and divided into three armies. The army of the Celt Bolgios invaded Macedon, defeating Ptolemy and beheading him. Another Celtic leader, Brennus, united all Celtic forces and moved into Central Greece. The barbarians ravaged the land and terrorized the local inhabitants.

In this time of crisis, the son of Demetrius Poliorcetes, Antigonus II, rose to the challenge. Antigonus was a trained warlord who had fought alongside his father in his various conflicts. Having held territory in Greece since the death of his father, Antigonus saw the opportunity to re-take the throne of Macedon during the Celtic invasion. It would be the Greek states, however, who would play the deceive role in the Celtic war.

Athens in particular played an important role in the defense in Greece. At the fourth battle of Thermopylae (279) the Athenians, allied with the Aetolian league, unsuccessfully fought against the army of Brennus. Celtic swords were devestating at close-quarters, which forced the Athenians to resort to skirmishing tactics. The decisive battle was at the Shrine of Delphi, where the allied Greek forces slaughtered the Celts after a night of terrible weather. In 277, Antigonus II ambushed and defeated a Celtic force on the Hellespont strait; that year he was crowned the King of Macedon at Pella. The Antigonid dynasty was again in control of Macedon. Although Greece had proved her martial spirit was still intact, Macedon would still lay claim over the Greek states to the south.

Some of the Celtic survivors migrated back north to Thrace, founding the city of Tylis. King Nicomdes of the Bythnian Kingdom (a new state in Asia minor) would help bring other Celts across the Aegean to serve as mercenaries. These Celts would later be called the Galatians and would have their own polity in the center of Anatolia.

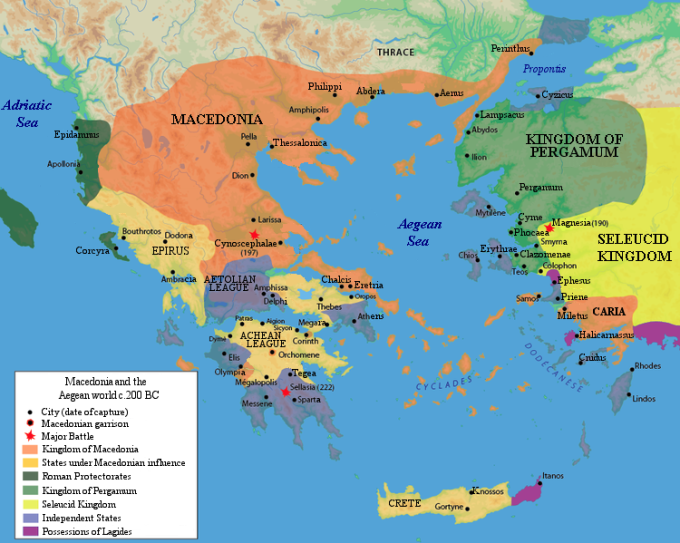

The Aetolian league rose up in revolt again in 200 BC, ending in the sack of an Athenian ally, Thermo. The Greek states remained under Macedonian rule. Phillip V, King of Macedon, had recently allied with the Carthaginians in their war against Rome. The Carthaginians under Hannibal were defeated decisively at Zama in 202 BC. Seeing Macedon in a vulnerable position, Athens decided that an alliance with Rome would hold the key to Greek freedom.

Sources:

George Grote- The History of Greece: Volume XII (1856)

Jon D. Mikalson- Religion in Hellenistic Athens (1998)

Hornblower and Spawforth- The Oxford Companion to Classical Civilization, p. 94-96 (Entry on Athenian History).

Xenophon’s Hellenica is one of the principal sources describing the Greek conflicts after the Peloponnesian War.

Absolutely loved this. I really want a continuation of Athens from 200 BC to 0 AD or so, as I am craving some more information. Thank you, I’ve been trying to find something like this for a while.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks James! Yeah this was our first post by in 2015, and I intended to return to the subject (the next part would feature the sacking of Athens under Sulla and the city under Roman rule) but the subject ended up getting shelved for the time being. In education, so much focus is placed on the Athenian golden age I definitely wanted to explore what happened after the Pelopponesian War, it’s a fascinating subject. I can provide a short summary:

Basically, After the Punic Wars, the Romans increasingly exerted influence over affairs in Greece, as the Greek city-states appealed to Rome to help throw of their Macedonian/Hellenistic overlords. This, and the fact that Philip V of Macedon allied with Carthage against Rome, led to the marginalization and then destruction of the Macedonian Kingdom.

The Greek city states found themselves “liberated” only to be under a much harsher master in the Romans. The Romans, at least during the late Republic, were very exploitative. So Athens eventually turned to Mithridates of Pontus, one of Rome’s greatest enemies (he supposedly initiated a region-wide uprising that killed 80,000 Romans in a single day). Long-story short, Mithridates got destroyed, and the Roman general Sulla sacked Athens. Greeks just couldn’t compete with the scale and tactics of Roman warfare (they could neither mobilize the same number of troops nor could they compete with the flexibility of the manipular legions).

Athens eventually recovered and remained a center for learning within the Roman Empire. Many Roman aristocrats went there for training in philosophy and rhetoric, though I believe Rhodes may have been favored for the latter. I think it would have been hard to find a good narrative about this period, besides when Hadrian visited in the second century.

Wrapping up classical antiquity, the Academy of Athens was closed by the Emperor Justinian in the 6th century, long after the city of Rome had fallen in the West. Eventually, the Greeks of Athens and the eastern Mediterranean came to see themselves very much as Romans, which effaced/absorbed their previous identity at least until the modern area.

I think more work could be done exploring how Athens fared during the barbarian invasions, and it’s role as a city in the Byzantine/Eastern Roman Empire. If I do return to this subject it might be some time, but thank you for reading!

LikeLike