By N.

Most famously known for their invasion of post-Roman Britain, the Saxons are a tribe important to Western history. Their interaction with the Romans in late antiquity characterized them as opportunistic pirates and raiders, yet they would go on to be a founding element of English civilization. Later, the Saxon Wars (772-804) with Charlemagne would be critical to the Christianization of central Europe; these conflicts would also presage the Viking raids that would devastate the Carolingian Empire. Here, I hope to give an account of Saxon history from the earliest times with a focus on their life on the European continent, though some discussion will be spent on their invasions of England.

The Saxons: Early Sources

The Saxons are first mentioned with certainty in history from the writings of Ptolemy (100-170 AD), a Greek Egyptian born under Roman rule in Alexandria. Ptolemy, in his tenth chapter of Geographia (150 AD)¸ writes about the Germanic peoples inhabiting the lands east of the Rhine river (Rhenus), north of the Danube (Danubius), and west of the Vistula. This work was written during the reign of Marcus Aurelius.

An earlier work, the Germania of Tacitus (written 98 AD), may possibly include some references to the Saxons or their precursors, though this is uncertain. Germania was completed during the reigns of either Nerva or Trajan. It is one of the only primary sources that deals solely with ancient Germanic peoples.

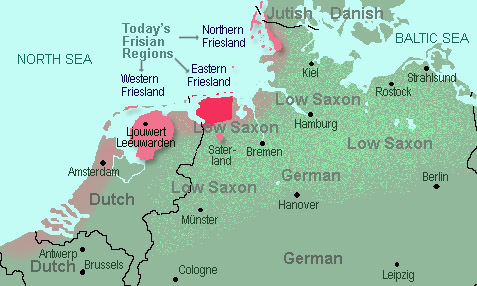

According to the Geographica, the Saxons (by 140 BC) inhabited the neck of the Jutland peninsula on the north side of the Elbe. In ancient times, the Jutland penninsula (now home to Denmark and the German state of Schleswig-Holstein) was called the Cimbric Chersonesus, after the Cimbri tribe. The Cimbri were infamous for their invasion of the Roman Republic in 113 BC, where they had only been defeated by the consul Marius with enormous Roman casualties. A number of Cimbri remained in the peninsula and survived the defeat of their brethren, and would have remained the northern neighbors of the early Saxons.

According to Sharon Turner, author of The History of the Anglo-Saxons (1805), the Saxons may have been related to a tribe called the Fosi. The Fosi are mentioned in Germania, but not in Ptolemy’s work. According to that work, the Fosi were allied with another Germanic tribe, the Cherusci, who had led the massacre of three Roman legions at the Battle of Teutoberg Forest in 9 AD. The Cherusci were eventually defeated by the Romans, who destroyed many of their villages and sold their inhabitants sold into slavery. The Cherusci went into decline and were taken advantage of by their tribal neighbors. Of the Fosi, Tacitus writes:

The downfall of the Cherusci brought with it also that of the Fosi, a neighboring tribe, which shared equally in their disasters, though they had been inferior to them in prosperous days.

It is possible that the Fosi were the fore-bearers of the Saxons in some way, and could have been the ancestors of a number of other later tribes. However, this is only speculation.

The Aviones are another tribe mentioned by Tacitus that could be related to the Saxons. Dr. Matthias Springer at the University of Magdeburg proposed that the Aviones mentioned by Tacitus were mistranslated by scribes over the centuries into Saxones printed by Ptolemy. What is noteworthy is that the word Aviones probably means Islander in proto-Germanic, and the Saxons are known from Ptolemy to have inhabited the small coastal islands offshore of the mouth of the Elbe.

Ptolemy’s Saxon Islands: Geography and History

The town of Büsum, formerly called Busen, was an island until 1585, when it was secured to the mainland by a dam. Like the Netherlands, the North Sea Coasts of Northwestern Germany are prone to flooding; historically, this region required intensive management to prevent disaster. In 1570, the All Saints Flood over-swept Büsum, killing many of the towns inhabitants. This incident, or other floods, inspired a popular German folk song Old Büsen. Today, the city has a population of approximately 5,000 and it remains a tourist destination for Hamburg residents.

Nordstrand, north of Büsum, was once part of a larger island called Strand; this island broke apart by the so-called Burchardi Flood of October 1634. This catastrophic flood destroyed over 13,000 homes, drowned 50,000 cattle and caused 6,000 human deaths. North on the peninsula is Elisabeth-Sophien-Koog, a tiny village founded after the 1634 flood, today with a population of 45. It is unlikely that the peninsula today bears much physical resemblance to the island known to the Saxons, besides the general character of the land. Today 2,200 people live in Nordstrand.

Helgoland is a small island located 30 miles from the German coast and has had a unique place in the regional culture of the area. The name means literally “sacred island.

Tacitus claims the the Islander tribes worshipped the Earth goddess Nerthus on the island, and described her rites as follows:

In an island of the ocean there is a sacred grove, and within it a consecrated chariot, covered over with a garment. Only one priest is permitted to touch it. He can perceive the presence of the goddess in this sacred recess, and walks by her side with the utmost reverence as she is drawn along by heifers. It is a season of rejoicing, and festivity reigns wherever she deigns to go and be received. They do not go to battle or wear arms; every weapon is under lock; peace and quiet are known and welcomed only at these times, till the goddess, weary of human intercourse, is at length restored by the same priest to her temple. Afterwards the car, the vestments, and, if you like to believe it, the divinity herself, are purified in a secret lake. Slaves perform the rite, who are instantly swallowed up by its waters. Hence arises a mysterious terror and a pious ignorance concerning the nature of that which is seen only by men doomed to die.

In the 8th century, a visitor to Helgoland saw the island was a cult center of the deity Fosete, guardian of Germanic law. Another visitor in the 11th century noted that the island was still revered by local sailors as a holy site. It can then be known that Helgoland was a site of religious significance to the ancient Saxons, and it was associated with one or more religious cults.

Sources:

Sharon Turner- The History of the Anglo-Saxons v. I (1799)

Dennis Howard Green, Frank Siegmund- The Continental Saxons, from the Migration Period to the Tenth Century (2003)

Germania from the Perseus Digital Library

All satellite images from Google Earth

Reblogged this on Die Goldene Landschaft.

LikeLike